Banksia Prionotes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Banksia prionotes'', commonly known as acorn banksia or orange banksia, is a species of

The most commonly reported

The most commonly reported  :''

:''

''Banksia prionotes'' × ''hookeriana'' has also been verified as occurring in the wild, but only in disturbed locations. The two parent species have overlapping ranges and are pollinated by the same

''Banksia prionotes'' × ''hookeriana'' has also been verified as occurring in the wild, but only in disturbed locations. The two parent species have overlapping ranges and are pollinated by the same

During data collection for ''

During data collection for ''

''Banksia prionotes'' occurs throughout much of the

''Banksia prionotes'' occurs throughout much of the

Flowering begins in February and is usually finished by the end of June. The species has an unusually low rate of flowering: even at the peak of its flowering season, it averages less than seven inflorescences per plant flowering at any one time. Individual flowers open sequentially from bottom to top within each inflorescence, the rate varying with the time of day: more flowers open during the day than at night, with a peak rate of around two to three florets per hour during the first few hours of daylight, when honeyeater foraging is also at its peak.

The flowers are fed at by a range of

Flowering begins in February and is usually finished by the end of June. The species has an unusually low rate of flowering: even at the peak of its flowering season, it averages less than seven inflorescences per plant flowering at any one time. Individual flowers open sequentially from bottom to top within each inflorescence, the rate varying with the time of day: more flowers open during the day than at night, with a peak rate of around two to three florets per hour during the first few hours of daylight, when honeyeater foraging is also at its peak.

The flowers are fed at by a range of

Like many plants in

Like many plants in

Described as "an outstanding ornamental species" by

Described as "an outstanding ornamental species" by

shrub

A shrub (often also called a bush) is a small-to-medium-sized perennial woody plant. Unlike herbaceous plants, shrubs have persistent woody stems above the ground. Shrubs can be either deciduous or evergreen. They are distinguished from trees ...

or tree

In botany, a tree is a perennial plant with an elongated stem, or trunk, usually supporting branches and leaves. In some usages, the definition of a tree may be narrower, including only woody plants with secondary growth, plants that are ...

of the genus ''Banksia

''Banksia'' is a genus of around 170 species in the plant family Proteaceae. These Australian wildflowers and popular garden plants are easily recognised by their characteristic flower spikes, and fruiting "cones" and heads. ''Banksias'' range i ...

'' in the family Proteaceae

The Proteaceae form a family of flowering plants predominantly distributed in the Southern Hemisphere. The family comprises 83 genera with about 1,660 known species. Together with the Platanaceae and Nelumbonaceae, they make up the order Pro ...

. It is native to the southwest

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

of Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

and can reach up to in height. It can be much smaller in more exposed areas or in the north of its range. This species has serrated, dull green leaves and large, bright flower spikes, initially white before opening to a bright orange. Its common name arises from the partly opened inflorescence

An inflorescence is a group or cluster of flowers arranged on a stem that is composed of a main branch or a complicated arrangement of branches. Morphologically, it is the modified part of the shoot of seed plants where flowers are formed o ...

, which is shaped like an acorn

The acorn, or oaknut, is the nut of the oaks and their close relatives (genera ''Quercus'' and '' Lithocarpus'', in the family Fagaceae). It usually contains one seed (occasionally

two seeds), enclosed in a tough, leathery shell, and borne ...

. The tree is a popular garden plant and also of importance to the cut flower industry

Cut flowers are flowers or flower buds (often with some stem and leaf) that have been cut from the plant bearing it. It is usually removed from the plant for decorative use. Typical uses are in vase displays, wreaths and garlands. Many gardener ...

.

''Banksia prionotes'' was first described in 1840 by English botanist John Lindley

John Lindley FRS (5 February 1799 – 1 November 1865) was an English botanist, gardener and orchidologist.

Early years

Born in Catton, near Norwich, England, John Lindley was one of four children of George and Mary Lindley. George Lindley w ...

, probably from material collected by James Drummond the previous year. There are no recognised varieties, although it has been known to hybridise with ''Banksia hookeriana

''Banksia hookeriana'', commonly known as Hooker's banksia, is a species of shrub of the genus ''Banksia'' in the family Proteaceae. It is native to the southwest of Western Australia and can reach up to high and wide. This species has long na ...

''. Widely distributed in south-west Western Australia

Names such as the South West or South West corner, when used to refer to a specific area of Western Australia, denote a region that has been defined in several different ways.

Such names now usually refer to areas immediately south of the Pert ...

, ''B. prionotes'' is found from Shark Bay

Shark Bay (Malgana: ''Gathaagudu'', "two waters") is a World Heritage Site in the Gascoyne region of Western Australia. The http://www.environment.gov.au/heritage/places/world/shark-bay area is located approximately north of Perth, on the ...

( 25° S) in the north, south as far as Kojonup (33°50′S). It grows exclusively in sandy soils, and is usually the dominant plant in scrubland

Shrubland, scrubland, scrub, brush, or bush is a plant community characterized by vegetation dominance (ecology), dominated by shrubs, often also including grasses, Herbaceous plant, herbs, and geophytes. Shrubland may either occur naturally or ...

or low woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with trees, or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the ''plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunlight and limited shade (see ...

. Pollinated

Pollination is the transfer of pollen from an anther of a plant to the stigma of a plant, later enabling fertilisation and the production of seeds, most often by an animal or by wind. Pollinating agents can be animals such as insects, birds, ...

by birds, it provides food for a wide array of vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

and invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

animals in the autumn and winter months. It is an important source of food for honeyeater

The honeyeaters are a large and diverse family (biology), family, Meliphagidae, of small to medium-sized birds. The family includes the Epthianura, Australian chats, myzomelas, friarbirds, wattlebirds, Manorina, miners and melidectes. They are ...

s (Meliphagidae), and is critical to their survival in the Avon Wheatbelt

The Avon Wheatbelt is a bioregion in Western Australia. It has an area of . It is considered part of the larger Southwest Australia savanna ecoregion.

Geography

The Avon Wheatbelt bioregion is mostly a gently undulating landscape with low reli ...

region, where it is the only nectar-producing plant in flower at some times of the year.

Description

''Banksia prionotes'' grows as a tree up to high in southern parts of its distribution, but in northern parts it is usually a shorter tree or spreading shrub, reaching about in height; it diminishes in size as the climate becomes warmer and drier further north. It has thin, mottled grey, smooth or grooved bark, andtomentose

Trichomes (); ) are fine outgrowths or appendages on plants, algae, lichens, and certain protists. They are of diverse structure and function. Examples are hairs, glandular hairs, scales, and papillae. A covering of any kind of hair on a pl ...

young stems. The alternate

Alternative or alternate may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* Alternative (''Kamen Rider''), a character in the Japanese TV series ''Kamen Rider Ryuki''

* ''The Alternative'' (film), a 1978 Australian television film

* ''The Alternative ...

dull green leaves are long, and wide, with toothed leaf margin

A leaf ( : leaves) is any of the principal appendages of a vascular plant stem, usually borne laterally aboveground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, ste ...

s made up of triangular lobes, and often a wavy surface.

Flowers occur in a typical ''Banksia'' flower spike, an inflorescence

An inflorescence is a group or cluster of flowers arranged on a stem that is composed of a main branch or a complicated arrangement of branches. Morphologically, it is the modified part of the shoot of seed plants where flowers are formed o ...

made up of hundreds of small individual flowers, or florets, densely packed around a cylindrical axis. ''B. prionotes'' has cream-coloured flowers with a bright orange limb that is not revealed until the flower fully opens. Known as anthesis

Anthesis is the period during which a flower is fully open and functional. It may also refer to the onset of that period.

The onset of anthesis is spectacular in some species. In ''Banksia'' species, for example, anthesis involves the extension ...

, this process sweeps through the inflorescence from bottom to top over a period of days, creating the effect of a cream inflorescence that progressively turns bright orange. The old flower parts fall away after flowering finishes, revealing the axis, which may bear up to 60 embedded follicles. Oval or oblong in shape and initially covered in fine hairs, these follicles are from long and wide, and protrude from the cone. Inside, they bear two seeds separated by a brownish woody seed separator

A seed separator is a structure found in the follicles of some Proteaceae. These follicles typically contain two seeds, with a seed separator between them. The seed separator is nothing but a little chip of wood, but in some cases it serves an i ...

. The matte blackish seeds are wedge-shaped (cuneate) and measure long by wide with a membranous 'wing'.

The root system consists of a main sinker root, and up to ten lateral root

Lateral roots, emerging from the pericycle (meristematic tissue), extend horizontally from the primary root (radicle) and over time makeup the iconic branching pattern of root systems. They contribute to anchoring the plant securely into the soil, ...

s extending from a non-lignotuber

A lignotuber is a woody swelling of the root crown possessed by some plants as a protection against destruction of the plant stem, such as by fire. Other woody plants may develop basal burls as a similar survival strategy, often as a response t ...

ous root crown

A root crown, also known as the root collar or root neck, is that part of a root system from which a stem arises. Since roots and stems have quite different vascular

The blood vessels are the components of the circulatory system that transport ...

. The main sinker root grows straight down to the water table; it may be up to long if the water table is that deep. Typically from in diameter immediately below the root crown, roots become gradually finer with depth, and may be less than half a centimetre (0.2 in) wide just above the water table. Upon reaching the water table, the sinker branches out into a network of very fine roots. The laterals radiate out horizontally from the base of the plant, at a depth of . They may extend over from the plant, and may bear secondary laterals; larger laterals often bear auxiliary sinker roots. Lateral roots seasonally form secondary rootlets from which grow dense surface mats of proteoid root

Cluster roots, also known as proteoid roots, are plant roots that form clusters of closely spaced short lateral rootlets. They may form a two- to five-centimetre-thick mat just beneath the leaf litter. They enhance nutrient uptake, possibly by ch ...

s, which function throughout the wetter months before dying off with the onset of summer.

Taxonomy

''Banksia prionotes'' was first published by English botanistJohn Lindley

John Lindley FRS (5 February 1799 – 1 November 1865) was an English botanist, gardener and orchidologist.

Early years

Born in Catton, near Norwich, England, John Lindley was one of four children of George and Mary Lindley. George Lindley w ...

in the January 1840 issue of his ''A Sketch of the Vegetation of the Swan River Colony

"A Sketch of the Vegetation of the Swan River Colony", also known by its standard botanical abbreviation ''Sketch Veg. Swan R.'', is an 1839 article by John Lindley on the flora of the Swan River Colony. Nearly 300 new species were published in it, ...

''; hence the species' standard author citation is ''Banksia prionotes'' Lindl. He did not specify the type material

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes t ...

upon which he based the species, but ''A Sketch of the Vegetation of the Swan River Colony'' is based primarily upon the collections of early settler and botanist James Drummond. A sheet of mounted specimens at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

Herbarium (CGE), labelled "Swan River, Drummond, 1839" and annotated "Banksia prionotes m" in Lindley's hand, has since been designated the lectotype

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes the ...

. Lindley also made no mention of the etymology

Etymology ()The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p. 633 "Etymology /ˌɛtɪˈmɒlədʒi/ the study of the class in words and the way their meanings have changed throughout time". is the study of the history of the Phonological chan ...

of the specific epithet

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

, ''"prionotes"'', but it is assumed to be derived from the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

''prion'' ("saw") and ''-otes'' ("quality"), referring to the serrated leaf margins.

The most commonly reported

The most commonly reported common name

In biology, a common name of a taxon or organism (also known as a vernacular name, English name, colloquial name, country name, popular name, or farmer's name) is a name that is based on the normal language of everyday life; and is often contrast ...

s of ''B. prionotes'' are acorn banksia, derived from the resemblance of partly opened inflorescences to acorn

The acorn, or oaknut, is the nut of the oaks and their close relatives (genera ''Quercus'' and '' Lithocarpus'', in the family Fagaceae). It usually contains one seed (occasionally

two seeds), enclosed in a tough, leathery shell, and borne ...

s; and orange banksia. Other reported common names include saw-toothed banksia and golden banksia ''Bwongka'' is a generic Noongar

The Noongar (, also spelt Noongah, Nyungar , Nyoongar, Nyoongah, Nyungah, Nyugah, and Yunga ) are Aboriginal Australian peoples who live in the south-west corner of Western Australia, from Geraldton on the west coast to Esperance on the so ...

name for ''Banksia'' in the Avon River catchment, where ''B. prionotes'' is one of several species occurring.

No further subspecies or varieties of ''B. prionotes'' have been described, and it has no taxonomic synonym

The Botanical and Zoological Codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

* In botanical nomenclature, a synonym is a scientific name that applies to a taxon that (now) goes by a different scientific name. For example, Linnae ...

s. Its only nomenclatural synonym is ''Sirmuellera prionotes'' (Lindl.) Kuntze, which arose from Otto Kuntze

Carl Ernst Otto Kuntze (23 June 1843 – 27 January 1907) was a German botanist.

Biography

Otto Kuntze was born in Leipzig.

An apothecary in his early career, he published an essay entitled ''Pocket Fauna of Leipzig''. Between 1863 and 1866 he ...

's unsuccessful 1891 attempt to transfer ''Banksia'' into the new name ''Sirmuellera''. When Carl Meissner

Carl Daniel Friedrich Meissner (1 November 1800 – 2 May 1874) was a Swiss botanist.

Biography

Born in Bern, Switzerland on 1 November 1800, he was christened Meisner but later changed the spelling of his name to Meissner. For most of his 40 ...

published his infrageneric arrangement of ''Banksia'' in 1856, he placed ''B. prionotes'' in section ''Eubanksia'' because its inflorescence is a spike rather than a domed head, and in series ''Salicinae'', a large series that is now considered quite heterogeneous. This series was discarded in the 1870 arrangement of George Bentham

George Bentham (22 September 1800 – 10 September 1884) was an English botanist, described by the weed botanist Duane Isely as "the premier systematic botanist of the nineteenth century". Born into a distinguished family, he initially studi ...

; instead, ''B. prionotes'' was placed in section ''Orthostylis'', which Bentham defined as consisting of those ''Banksia'' species with flat leaves with serrated margins, and rigid, erect styles that "give the cones after the flowers have opened a different aspect". In 1981, Alex George published a revised arrangement that placed ''B. prionotes'' in the subgenus ''Banksia'' because of its flower spike, section ''Banksia'' because its styles are straight rather than hooked, and the series ''Crocinae'', a new series of four closely related species, all with bright orange perianth

The perianth (perigonium, perigon or perigone in monocots) is the non-reproductive part of the flower, and structure that forms an envelope surrounding the sexual organs, consisting of the calyx (sepals) and the corolla (petals) or tepals when ...

s and pistil

Gynoecium (; ) is most commonly used as a collective term for the parts of a flower that produce ovules and ultimately develop into the fruit and seeds. The gynoecium is the innermost whorl of a flower; it consists of (one or more) ''pistils'' ...

s.

George's arrangement remained current until 1996, when Kevin Thiele

Kevin R. Thiele is currently an adjunct associate professor at the University of Western Australia and the director of Taxonomy Australia. He was the curator of the Western Australian Herbarium from 2006 to 2015. His research interests include ...

and Pauline Ladiges

Pauline Yvonne Ladiges (born 1948) is a botanist whose contributions have been significant both in building the field of taxonomy, ecology and historical biogeography of Australian plants, particularly Eucalypts and flora, and in science educa ...

published an arrangement informed by a cladistic

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups (" clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived char ...

analysis of morphological characteristics. Their arrangement maintained ''B. prionotes'' in ''B.'' subg. ''Banksia'', but discarded George's sections and his series ''Crocinae''. Instead, ''B. prionotes'' was placed at the end of series ''Banksia'', in subseries ''Cratistylis''. Questioning the emphasis on cladistics in Thiele and Ladiges' arrangement, George published a slightly modified version of his 1981 arrangement in his 1999 treatment of ''Banksia'' for the ''Flora of Australia

The flora of Australia comprises a vast assemblage of plant species estimated to over 30,000 vascular and 14,000 non-vascular plants, 250,000 species of fungi and over 3,000 lichens. The flora has strong affinities with the flora of Gondwana, ...

'' series of monographs. To date, this remains the most recent comprehensive arrangement. The placement of ''B. prionotes'' in George's 1999 arrangement may be summarised as follows:

:''

:''Banksia

''Banksia'' is a genus of around 170 species in the plant family Proteaceae. These Australian wildflowers and popular garden plants are easily recognised by their characteristic flower spikes, and fruiting "cones" and heads. ''Banksias'' range i ...

''

:: ''B.'' subg. ''Banksia''

::: ''B.'' sect. ''Banksia''

:::: ''B.'' ser. ''Salicinae'' (11 species, 7 subspecies)

:::: ''B.'' ser. ''Grandes'' (2 species)

:::: ''B.'' ser. ''Banksia'' (8 species)

:::: ''B.'' ser. ''Crocinae''

:::::''B. prionotes''

:::::'' B. burdettii''

:::::'' B. hookeriana''

:::::'' B. victoriae''

:::: ''B.'' ser. ''Prostratae'' (6 species, 3 varieties)

:::: ''B.'' ser. ''Cyrtostylis'' (13 species)

:::: ''B.'' ser. ''Tetragonae'' (3 species)

:::: ''B.'' ser. ''Bauerinae'' (1 species)

:::: ''B.'' ser. ''Quercinae'' (2 species)

::: ''B.'' sect. ''Coccinea'' (1 species)

::: ''B.'' sect. ''Oncostylis'' (4 series, 22 species, 4 subspecies, 11 varieties)

:: ''B.'' subg. ''Isostylis'' (3 species)

Since 1998, American botanist Austin Mast Austin R. Mast is a research botanist. Born in 1972, he obtained a Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 2000. He is currently a professor within the Department of Biological Science at Florida State University (FSU), and has been dire ...

has been publishing results of ongoing cladistic analyses of DNA sequence

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. Th ...

data for the subtribe Banksiinae

''Banksia'' is a genus of around 170 species in the plant family Proteaceae. These Australian wildflowers and popular garden plants are easily recognised by their characteristic flower spikes, and fruiting "cones" and heads. ''Banksias'' range ...

, which includes ''Banksia''. With respect to ''B. prionotes'', Mast's results are fairly consistent with those of both George and Thiele and Ladiges. Series ''Crocinae'' appears to be monophyletic

In cladistics for a group of organisms, monophyly is the condition of being a clade—that is, a group of taxa composed only of a common ancestor (or more precisely an ancestral population) and all of its lineal descendants. Monophyletic gro ...

, and '' B. hookeriana'' is confirmed as ''B. prionotes'' closest relative. Overall, however, the inferred phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

is very different from George's arrangement. Early in 2007, Mast and Thiele initiated a rearrangement of ''Banksiinae'' by publishing several new names, including subgenus ''Spathulatae'' for the species of ''Banksia'' that have spoon-shaped cotyledon

A cotyledon (; ; ; , gen. (), ) is a significant part of the embryo within the seed of a plant, and is defined as "the embryonic leaf in seed-bearing plants, one or more of which are the first to appear from a germinating seed." The numb ...

s; in this way they also redefined the autonym

Autonym may refer to:

* Autonym, the name used by a person to refer to themselves or their language; see Exonym and endonym

* Autonym (botany), an automatically created infrageneric or infraspecific name

See also

* Nominotypical subspecies, in zo ...

''B.'' subgenus ''Banksia''. They have not yet published a full arrangement, but if their nomenclatural changes are taken as an interim arrangement, then ''B. prionotes'' is placed in subgenus ''Banksia''.

Hybrids

With ''Banksia hookeriana''

''Banksia prionotes'' readily hybridises with ''Banksia hookeriana

''Banksia hookeriana'', commonly known as Hooker's banksia, is a species of shrub of the genus ''Banksia'' in the family Proteaceae. It is native to the southwest of Western Australia and can reach up to high and wide. This species has long na ...

'' (Hooker's banksia) under experimental conditions, indicating that these species have highly compatible pollen. The cultivar

A cultivar is a type of cultivated plant that people have selected for desired traits and when propagated retain those traits. Methods used to propagate cultivars include: division, root and stem cuttings, offsets, grafting, tissue culture, ...

''B.'' 'Waite Orange' is believed to be such a hybrid, having arisen by open pollination

"Open pollination" and "open pollinated" refer to a variety of concepts in the context of the sexual reproduction of plants. Generally speaking, the term refers to plants pollinated naturally by birds, insects, wind, or human hands.

True-breedi ...

during a breeding experiment conducted at the Waite Agricultural Research Institute

The University of Adelaide (informally Adelaide University) is a public research university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third-oldest university in Australia. The university's main campus is located on N ...

of the University of Adelaide

The University of Adelaide (informally Adelaide University) is a public research university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third-oldest university in Australia. The university's main campus is located on N ...

in 1988.

''Banksia prionotes'' × ''hookeriana'' has also been verified as occurring in the wild, but only in disturbed locations. The two parent species have overlapping ranges and are pollinated by the same

''Banksia prionotes'' × ''hookeriana'' has also been verified as occurring in the wild, but only in disturbed locations. The two parent species have overlapping ranges and are pollinated by the same honeyeater

The honeyeaters are a large and diverse family (biology), family, Meliphagidae, of small to medium-sized birds. The family includes the Epthianura, Australian chats, myzomelas, friarbirds, wattlebirds, Manorina, miners and melidectes. They are ...

species; and though preferring different soils, they often occur near enough to each other for pollinators to move between them. It therefore appears that the only barrier to hybridisation in undisturbed areas is the different flowering seasons: ''B. prionotes'' has usually finished flowering by the end of May, whereas flowering of ''B. hookeriana'' usually does not begin until June. In disturbed areas, however, the increased runoff and reduced competition mean extra nutrients are available, and this results in larger plants with more flowers and a longer flowering season. Thus the flowering seasons overlap, and the sole barrier to interbreeding is removed. The resultant F1 hybrid

An F1 hybrid (also known as filial 1 hybrid) is the first filial generation of offspring of distinctly different parental types. F1 hybrids are used in genetics, and in selective breeding, where the term F1 crossbreed may be used. The term is somet ...

s are fully fertile, with seed production rates similar to that of the parent species. There is no barrier to backcrossing of hybrids with parent species, and in some populations this has resulted in hybrid swarm

A hybrid swarm is a population of hybrids that has survived beyond the initial hybrid generation, with interbreeding between hybrid individuals and backcrossing with its parent types. Such population are highly variable, with the genetic and phe ...

s. This raises the possibility of the parent species gradually losing their genetic integrity, especially if the intermediate characteristics of the hybrid offer it a competitive advantage over the parent species, such as a wider habitat tolerance. Moreover, speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution within ...

might occur if the hybrid's intermediate characteristics allow it to occupy a habitat unsuited to both parents, such as an intermediate soil type.

''Banksia prionotes'' × ''hookeriana'' hybrids have characteristics intermediate between the two parents. For example, the first putative hybrids studied had a habit "like that of gigantic ''B. hookerana'' ic, having inherited the size of ''B. prionotes'', together with ''B. hookeriana''s tendency to branch from near the base of the trunk. Similarly, the infructescences were like ''B. prionotes'' in size, but had persistent flowers like ''B. hookeriana''. Inflorescences and leaves were intermediate in size and shape, and bark was like that of ''B. prionotes''.

Other putative hybrids

During data collection for ''

During data collection for ''The Banksia Atlas

''The Banksia Atlas'' is an atlas that documents the ranges, habitats and growth forms of various species and other subgeneric taxa of ''Banksia'', an iconic Australian wildflower genus. First published in 1988, it was the result of a three-ye ...

'' project, a single presumed natural hybrid between ''B. prionotes'' and '' B. lindleyana'' (porcupine banksia), with fruit like ''B. lindleyana'' but leaves intermediate between the two parents, was found north of Kalbarri National Park

Kalbarri National Park is located north of Perth, in the Mid West region of Western Australia.

The major geographical features of the park include the Murchison River gorge which runs for nearly on the lower reaches of the Murchison River. Sp ...

. At the time this was considered an important discovery, as the parent species were thought not to be closely related. Mast's analyses, however, place them both in a clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

of eight species, though ''B. lindleyana'' remains less closely related to ''B. prionotes'' than ''B. hookeriana''. Hybrids of ''B. prionotes'' with '' B. menziesii'' (firewood banksia) have also been produced by artificial means, and presumed natural hybrids have been recorded.

Distribution and habitat

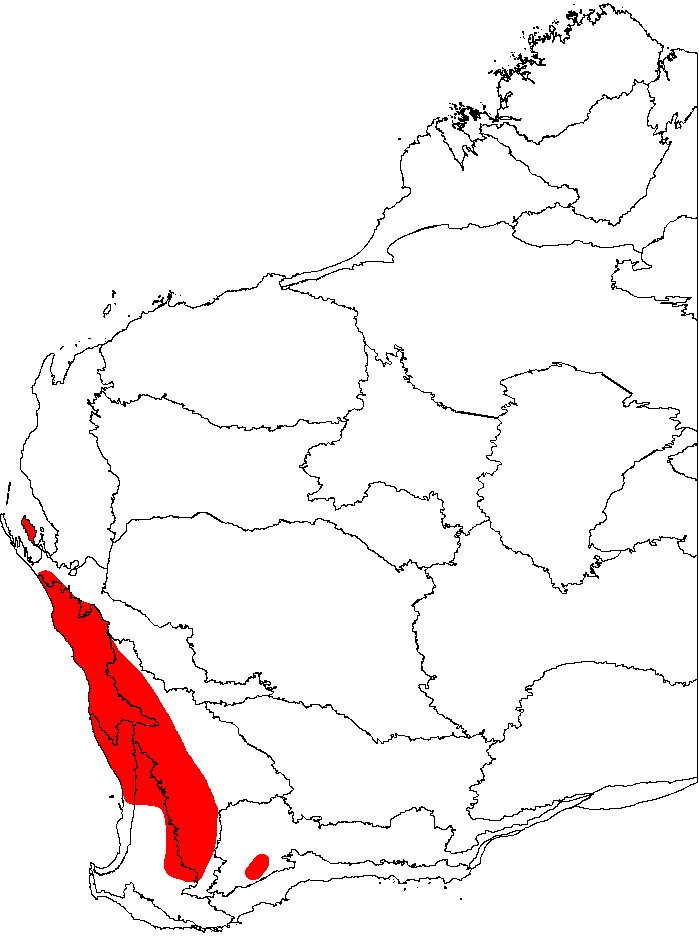

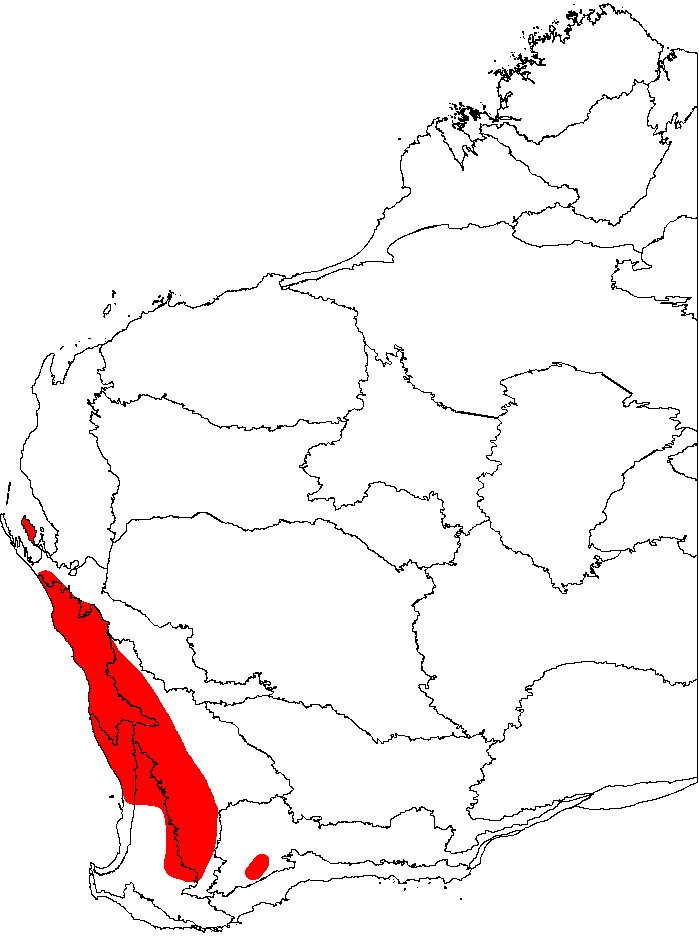

''Banksia prionotes'' occurs throughout much of the

''Banksia prionotes'' occurs throughout much of the Southwest Botanical Province

Southwest Australia is a ecoregion, biogeographic region in Western Australia. It includes the Mediterranean climate, Mediterranean-climate area of southwestern Australia, which is home to a diverse and distinctive flora and fauna.

The region i ...

, occurring both along the west coast and well inland, and ranging from Shark Bay

Shark Bay (Malgana: ''Gathaagudu'', "two waters") is a World Heritage Site in the Gascoyne region of Western Australia. The http://www.environment.gov.au/heritage/places/world/shark-bay area is located approximately north of Perth, on the ...

(25°30′S) in the north, to Kojonup (33°50'S) and Jerramungup (34°24'S 118°55'E) in the south and south-east respectively. It grows among tall shrubland

Shrubland, scrubland, scrub, brush, or bush is a plant community characterized by vegetation dominated by shrubs, often also including grasses, herbs, and geophytes. Shrubland may either occur naturally or be the result of human activity. It m ...

or low woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with trees, or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the ''plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunlight and limited shade (see ...

, mostly in the swale

Swale or Swales may refer to:

Topography

* Swale (landform), a low tract of land

** Bioswale, landform designed to remove silt and pollution

** Swales, found in the formation of Hummocky cross-stratification

Geography

* River Swale, in North ...

s and lower slopes of dune

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, f ...

s, and shows a very strong preference for deep white or yellow sand.

It is most common amongst the kwongan heath of the Geraldton Sandplains

Geraldton (Wajarri: ''Jambinu'', Wilunyu: ''Jambinbirri'') is a coastal city in the Mid West region of the Australian state of Western Australia, north of the state capital, Perth.

At June 2018, Geraldton had an urban population of 37,648. ...

north of Jurien; it has a fairly continuous distribution there, often as the dominant species, and extends inland to around the 350 mm isohyet

A contour line (also isoline, isopleth, or isarithm) of a function of two variables is a curve along which the function has a constant value, so that the curve joins points of equal value. It is a plane section of the three-dimensional graph ...

. On the Swan Coastal Plain

The Swan Coastal Plain in Western Australia is the geographic feature which contains the Swan River as it travels west to the Indian Ocean. The coastal plain continues well beyond the boundaries of the Swan River and its tributaries, as a geol ...

to the south, its distribution is discontinuous, being largely confined to patches of suitable sand in the narrow transition zone where tuart forest

Tuart forest is an open forest in which the dominant overstorey tree is ''Eucalyptus gomphocephala'' (tuart). This form of vegetation occurs only in the Southwest Botanical Province of Western Australia. Tuart being predominantly a coastal tree, t ...

gives way to jarrah forest

Jarrah forest is tall open forest in which the dominant overstory tree is ''Eucalyptus marginata'' (jarrah). The ecosystem occurs only in the Southwest Botanical Province of Western Australia. It is most common in the biogeographic region named in ...

. With the exception of a population at Point Walter

Point Walter (Noongar: ''Dyoondalup'') is a point on the Swan River, Western Australia, notable for its large sandbar that extends into the river. It is located on the southern shore of Melville Water, and forms its western end. Point Walter ...

(32°00′S), it does not occur on the sandplain south of the Swan River.

The soils east of the Darling Scarp

The Darling Scarp, also referred to as the Darling Range or Darling Ranges, is a low escarpment running north–south to the east of the Swan Coastal Plain and Perth, Western Australia. The escarpment extends generally north of Bindoon, to th ...

are generally too heavy for this species, with the exception of some isolated pockets of deep alluvial

Alluvium (from Latin ''alluvius'', from ''alluere'' 'to wash against') is loose clay, silt, sand, or gravel that has been deposited by running water in a stream bed, on a floodplain, in an alluvial fan or beach, or in similar settings. Alluv ...

or aeolian yellow sand. ''B. prionotes'' thus has a very patchy distribution east of the scarp. This area nonetheless accounts for around half of its geographic range, with the species extending well to the south and south-east of the scarp. In total, the species occurs over a north–south distance of about , and an east–west distance of about .

The species is almost totally restricted to the swales and lower slopes of dunes. Various reasons for this have been proposed; on the one hand, it has been argued that its dependence on ground water necessitates that it grow only where ground water is relatively near the surface; on the other hand, it has been suggested that it cannot survive in higher parts of the landscape because fires are too frequent there. The latter hypothesis is supported by the recent expansion of ''B. prionotes'' along road verges of the Brand Highway

Brand Highway is a main highway linking the northern outskirts of Perth to Geraldton in Western Australia. Together with North West Coastal Highway, it forms part of the Western Australian coastal link to the Northern Territory. The highw ...

, where fires are relatively rare. Despite ''B. prionotes'' occurrence in lower parts of the landscape, it does not occur in areas prone to flooding, because of its intolerance of heavy soils, and because extended periods of flooding kill seedlings. However, recent falls of the water table on the Swan Coastal Plain have seen ''B. prionotes'' replace the more water-loving ''Banksia littoralis

''Banksia littoralis'', commonly known as the swamp banksia, swamp oak, river banksia or seaside banksia and the western swamp banksia, is a species of tree that is Endemism, endemic to the south-west of Western Australia. The Noongar peoples ...

'' in some areas that were previously flood-prone.

Ecology and physiology

Growth

The structure of the root system, comprising a vertical tap root and multiple horizontal laterals, develops in the seedling's first year. Thereafter, the sinker and laterals continue to lengthen, and new laterals appear. There are only three to five laterals at first, but this number typically increases to eight to ten within ten years. During the first winter, there is a great deal of root system development, especially elongation of the sinker root, but almost no shoot growth. By summer, the sinker root has generally almost reached the water table, and shoot growth increases substantially. Around February, the shoot forms a resting bud, and growth then ceases until October. On resumption of shoot growth, the shoots grow rapidly for a short time, while the plant is under little water stress; then, with the onset of water stress, the plants settles into a long period of slower shoot growth. This pattern of summer-only shoot growth is maintained throughout the life of the plant, except that in mature plants, seasonal shoot growth may cease with the formation of a terminal inflorescence rather than a resting bud. Inflorescence development continues after shoot growth ceases, and flowering commences in February or March. March and April are the peak months for flowering, which ends in July or August. Annual growth increases exponentially for the first eight years or so, but then slows down as resources are diverted into reproduction and the greater density of foliage results in reducedphotosynthetic

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored in c ...

efficiency

Efficiency is the often measurable ability to avoid wasting materials, energy, efforts, money, and time in doing something or in producing a desired result. In a more general sense, it is the ability to do things well, successfully, and without ...

.

Nutrition and metabolism

The root structure of ''B. prionotes'' exhibits two common environmental adaptations. Firstly, this species is phreatophytic, that is, its long taproot extends down to the water table, securing it a continuous water supply through the dry summer months, when surface water is generally unavailable. This not only helps ensure survival over summer, but allows plants to grow then. Though the supply of water is the taproot's primary function, the ground water obtained typically containsion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conven ...

ic concentrations of chloride

The chloride ion is the anion (negatively charged ion) Cl−. It is formed when the element chlorine (a halogen) gains an electron or when a compound such as hydrogen chloride is dissolved in water or other polar solvents. Chloride salts ...

, sodium

Sodium is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin ''natrium'') and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 of the periodic table. Its only stable iso ...

, magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element with the symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 of the periodic ta ...

, calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to ...

and potassium

Potassium is the chemical element with the symbol K (from Neo-Latin ''kalium'') and atomic number19. Potassium is a silvery-white metal that is soft enough to be cut with a knife with little force. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmosphe ...

that are adequate for the plant's nutritional needs.

The other common adaptation is the possession of cluster root

Cluster roots, also known as proteoid roots, are plant roots that form clusters of closely spaced short lateral rootlets. They may form a two- to five-centimetre-thick mat just beneath the leaf litter. They enhance nutrient uptake, possibly by chem ...

s, which allow it to extract enough nutrients to survive in the oligotroph

An oligotroph is an organism that can live in an environment that offers very low levels of nutrients. They may be contrasted with copiotrophs, which prefer nutritionally rich environments. Oligotrophs are characterized by slow growth, low rates of ...

ic soils in which it grows. With the onset of autumn rains, the lateral roots form dense surface mats of cluster roots in the top of soil, just below the leaf litter, where most minerals are concentrated. These roots exude chemicals that enhance mineral solubility

In chemistry, solubility is the ability of a substance, the solute, to form a solution with another substance, the solvent. Insolubility is the opposite property, the inability of the solute to form such a solution.

The extent of the solubil ...

, greatly increasing the availability and uptake of nutrient

A nutrient is a substance used by an organism to survive, grow, and reproduce. The requirement for dietary nutrient intake applies to animals, plants, fungi, and protists. Nutrients can be incorporated into cells for metabolic purposes or excret ...

s in impoverished soils such as the phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ear ...

-deficient native soils of Australia. For as long as surface water

Surface water is water located on top of land forming terrestrial (inland) waterbodies, and may also be referred to as ''blue water'', opposed to the seawater and waterbodies like the ocean.

The vast majority of surface water is produced by prec ...

is available, they take in water and a range of minerals. In ''B. prionotes'' they are principally responsible for the uptake of malate

Malic acid is an organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a dicarboxylic acid that is made by all living organisms, contributes to the sour taste of fruits, and is used as a food additive. Malic acid has two stereoisomeric forms (L ...

, phosphate, chloride, sodium and potassium. When soils are high in nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion

A polyatomic ion, also known as a molecular ion, is a covalent bonded set of two or more atoms, or of a metal complex, that can be considered to behave as a single unit and that has a net charge that is not zer ...

s, they may also perform some nitrate reductase

Nitrate reductases are molybdoenzymes that reduce nitrate (NO) to nitrite (NO). This reaction is critical for the production of protein in most crop plants, as nitrate is the predominant source of nitrogen in fertilized soils.

Types

Euka ...

activities, primarily the conversion of ammonium

The ammonium cation is a positively-charged polyatomic ion with the chemical formula or . It is formed by the protonation of ammonia (). Ammonium is also a general name for positively charged or protonated substituted amines and quaternary a ...

into amino acids

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

such as asparagine

Asparagine (symbol Asn or N) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the depro ...

and glutamine

Glutamine (symbol Gln or Q) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Its side chain is similar to that of glutamic acid, except the carboxylic acid group is replaced by an amide. It is classified as a charge-neutral, ...

.

The uptake of nutrient and water by the cluster roots peaks through winter and spring, but ceases when the upper layer of soil dries out in summer. The cluster roots are then allowed to die, but the laterals are protected from desiccation by a continuous supply of water from the sinker root. The water supplied to the laterals by the sinker root is continually lost to the soil; thus this plant facilitates the movement of ground water from the water table into surface soil, a process known as hydraulic redistribution Hydraulic redistribution is a passive mechanism where water is transported from moist to dry soils via subterranean networks. It occurs in vascular plants that commonly have roots in both wet and dry soils, especially plants with both taproots that ...

. Cluster roots have been estimated as comprising about 30% of total root biomass in this species; the seasonal production of so much biomass

Biomass is plant-based material used as a fuel for heat or electricity production. It can be in the form of wood, wood residues, energy crops, agricultural residues, and waste from industry, farms, and households. Some people use the terms bi ...

, only for it to be lost at the end of the growing season, represents a substantial investment by the plant, but one that is critical in the competition for nutrients.

During winter, asparagine is metabolised immediately, but other nutrients, especially phosphates and glutamine, are removed from the xylem sap

Sap is a fluid transported in xylem cells (vessel elements or tracheids) or phloem sieve tube elements of a plant. These cells transport water and nutrients throughout the plant.

Sap is distinct from latex, resin, or cell sap; it is a sepa ...

and stored in mature stem

Stem or STEM may refer to:

Plant structures

* Plant stem, a plant's aboveground axis, made of vascular tissue, off which leaves and flowers hang

* Stipe (botany), a stalk to support some other structure

* Stipe (mycology), the stem of a mushro ...

, bark and leaf

A leaf ( : leaves) is any of the principal appendages of a vascular plant stem, usually borne laterally aboveground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, ste ...

tissues for release back into the xylem

Xylem is one of the two types of transport tissue in vascular plants, the other being phloem. The basic function of xylem is to transport water from roots to stems and leaves, but it also transports nutrients. The word ''xylem'' is derived from ...

just before shoot growth begins in mid summer. This is also the time when the oldest leaves senesce and die, returning nutrients to the plant at the time when they are needed most. When glutamine eventually reaches the leaves, it is broken down and used to synthesise protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

and non-amide

In organic chemistry, an amide, also known as an organic amide or a carboxamide, is a compound with the general formula , where R, R', and R″ represent organic groups or hydrogen atoms. The amide group is called a peptide bond when it is ...

amino acids such as aspartate

Aspartic acid (symbol Asp or D; the ionic form is known as aspartate), is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Like all other amino acids, it contains an amino group and a carboxylic acid. Its α-amino group is in the pro ...

, threonine

Threonine (symbol Thr or T) is an amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH form under biological conditions), a carboxyl group (which is in the deprotonated −COO� ...

, serine

Serine (symbol Ser or S) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated − form under biological conditions), a carboxyl group (which is in the deprotonated − form un ...

, glutamate

Glutamic acid (symbol Glu or E; the ionic form is known as glutamate) is an α-amino acid that is used by almost all living beings in the biosynthesis of proteins. It is a non-essential nutrient for humans, meaning that the human body can syn ...

, glycine

Glycine (symbol Gly or G; ) is an amino acid that has a single hydrogen atom as its side chain. It is the simplest stable amino acid (carbamic acid is unstable), with the chemical formula NH2‐ CH2‐ COOH. Glycine is one of the proteinogeni ...

, alanine

Alanine (symbol Ala or A), or α-alanine, is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an amine group and a carboxylic acid group, both attached to the central carbon atom which also carries a methyl group side c ...

and cystine

Cystine is the oxidized derivative of the amino acid cysteine and has the formula (SCH2CH(NH2)CO2H)2. It is a white solid that is poorly soluble in water. As a residue in proteins, cystine serves two functions: a site of redox reactions and a me ...

. Together with sucrose

Sucrose, a disaccharide, is a sugar composed of glucose and fructose subunits. It is produced naturally in plants and is the main constituent of white sugar. It has the molecular formula .

For human consumption, sucrose is extracted and refined ...

and other solutes

In chemistry, a solution is a special type of homogeneous mixture composed of two or more substances. In such a mixture, a solute is a substance dissolved in another substance, known as a solvent. If the attractive forces between the solvent ...

, these are then circulated in the phloem

Phloem (, ) is the living biological tissue, tissue in vascular plants that transports the soluble organic compounds made during photosynthesis and known as ''photosynthates'', in particular the sugar sucrose, to the rest of the plant. This tran ...

. The phloem sap of ''B. prionotes'' is unusual in having an extremely low ratio of potassium to sodium cation

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

s, and very low concentrations of phosphate and amino acids compared to chloride and sulfate anion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

s. The low levels of potassium and phosphate reflect the extremely low availability of these minerals in the soil. The unusually high levels of sodium and chloride—at concentrations usually only seen under saline conditions—may be due to the necessity of maintaining turgor pressure

Turgor pressure is the force within the cell that pushes the plasma membrane against the cell wall.

It is also called ''hydrostatic pressure'', and is defined as the pressure in a fluid measured at a certain point within itself when at equilibri ...

; that is, with so little potassium and phosphate available, and that needed in the building of new tissue, ''B. prionotes'' is forced to circulate whatever other ions are available in order to maintain turgor.

Breeding system

Flowering begins in February and is usually finished by the end of June. The species has an unusually low rate of flowering: even at the peak of its flowering season, it averages less than seven inflorescences per plant flowering at any one time. Individual flowers open sequentially from bottom to top within each inflorescence, the rate varying with the time of day: more flowers open during the day than at night, with a peak rate of around two to three florets per hour during the first few hours of daylight, when honeyeater foraging is also at its peak.

The flowers are fed at by a range of

Flowering begins in February and is usually finished by the end of June. The species has an unusually low rate of flowering: even at the peak of its flowering season, it averages less than seven inflorescences per plant flowering at any one time. Individual flowers open sequentially from bottom to top within each inflorescence, the rate varying with the time of day: more flowers open during the day than at night, with a peak rate of around two to three florets per hour during the first few hours of daylight, when honeyeater foraging is also at its peak.

The flowers are fed at by a range of nectarivorous

In zoology, a nectarivore is an animal which derives its energy and nutrient requirements from a diet consisting mainly or exclusively of the sugar-rich nectar produced by flowering plants.

Nectar as a food source presents a number of benefits a ...

birds: mainly honeyeaters

The honeyeaters are a large and diverse family, Meliphagidae, of small to medium-sized birds. The family includes the Australian chats, myzomelas, friarbirds, wattlebirds, miners and melidectes. They are most common in Australia and New Guinea ...

, including the New Holland honeyeater (''Phylidonyris novaehollandiae''), white-cheeked honeyeater

The white-cheeked honeyeater (''Phylidonyris niger'') inhabits the east coast and the south-west corner of Australia. It has a large white patch on its cheek, brown eyes, and a yellow panel on its wing.

Taxonomy

The white-cheeked honeyeater was ...

(''P. nigra''), brown honeyeater

The brown honeyeater (''Lichmera indistincta'') is a species of bird in the family Meliphagidae. It belongs to the honeyeaters, a group of birds which have highly developed brush-tipped tongues adapted for nectar feeding. Honeyeaters are found ...

(''Lichmera indistincta''), singing honeyeater

The singing honeyeater (''Gavicalis virescens'') is a small bird found in Australia, and is part of the honeyeater family Meliphagidae. The bird lives in a wide range of shrubland, woodland, and coastal habitat. It is relatively common and is wi ...

(''Lichenostomus virescens''), tawny-crowned honeyeater (''Gliciphila melanops'') and red wattlebird

The red wattlebird (''Anthochaera carunculata'') is a passerine bird native to southern Australia. At in length, it is the second largest species of Australian honeyeater. It has mainly grey-brown plumage, with red eyes, distinctive pinkish-re ...

(''Anthochaera carunculata''). Lorikeets

Loriini is a tribe of small to medium-sized arboreal parrots characterized by their specialized brush-tipped tongues for feeding on nectar of various blossoms and soft fruits, preferably berries. The species form a monophyletic group within the ...

have also been observed feeding at the flowers, as have insects, including ants, bees, and aphid

Aphids are small sap-sucking insects and members of the superfamily Aphidoidea. Common names include greenfly and blackfly, although individuals within a species can vary widely in color. The group includes the fluffy white woolly aphids. A t ...

s. Of these, evidence suggests that only birds are effective pollinators. Insects apparently play no role in pollination, since inflorescences do not form follicles when birds are excluded in pollinator exclusion experiment Pollinator exclusion experiments are experiments used by ecologists to determine the effectiveness of putative plant pollination vectors. Essentially, certain pollinators are prevented from visiting certain flowers, and observations are then made on ...

s; and pollination by mammals has never been recorded in this species.

Honeyeaters prefer to forage at individual flowers which have only just opened, as these offer the most nectar

Nectar is a sugar-rich liquid produced by plants in glands called nectaries or nectarines, either within the flowers with which it attracts pollinating animals, or by extrafloral nectaries, which provide a nutrient source to animal mutualists ...

. As they probe for nectar, honeyeaters end up with large quantities of pollen on their beaks, foreheads and throats, some of which they subsequently transfer to other flowers. This transfer is quite efficient: flowers typically lose nearly all their pollen within four hours of opening, and pollen is deposited on the majority of stigmata. Around 15% of these stigmata end up with pollen lodged in the stigmatic groove, a prerequisite to fertilisation.

The structure of the ''Banksia'' flower, with the style end functioning as a pollen presenter

A pollen-presenter is an area on the tip of the style in flowers of plants of the family Proteaceae on which the anthers release their pollen prior to anthesis. To ensure pollination, the style grows during anthesis, sticking out the pollen-present ...

, suggests that autogamous

Autogamy, or self-fertilization, refers to the fusion of two gametes that come from one individual. Autogamy is predominantly observed in the form of self-pollination, a reproductive mechanism employed by many flowering plants. However, species of ...

self-fertilisation

Autogamy, or self-fertilization, refers to the fusion of two gametes that come from one individual. Autogamy is predominantly observed in the form of self-pollination, a reproductive mechanism employed by many flowering plants. However, species of ...

must be common. In many ''Banksia'' species, the risk of this occurring is reduced by protandry

Sequential hermaphroditism (called dichogamy in botany) is a type of hermaphroditism that occurs in many fish, gastropods, and plants. Sequential hermaphroditism occurs when the individual changes its sex at some point in its life. In particular, ...

: a delay in a flower's receptivity to pollen until after its own pollen has lost its viability. There is dispute, however, over whether this occurs in ''B. prionotes'': one study claimed to have confirmed "protandrous development", yet recorded high levels of stigmatic receptivity immediately after anthesis

Anthesis is the period during which a flower is fully open and functional. It may also refer to the onset of that period.

The onset of anthesis is spectacular in some species. In ''Banksia'' species, for example, anthesis involves the extension ...

, and long pollen viability, observations that are not consistent with protandry.

If it does occur, protandry does nothing to prevent geitonogamous self-pollination: that is, pollination with pollen from another flower on the same plant. In fact, when birds forage at ''B. prionotes'', only about a quarter of all movements from inflorescence to inflorescence involve a change of plant. Geitonogamous self-pollination must therefore occur more often in this species than cross-pollination

Pollination is the transfer of pollen from an anther of a plant to the stigma of a plant, later enabling fertilisation and the production of seeds, most often by an animal or by wind. Pollinating agents can be animals such as insects, birds, ...

. This does not imply high rates of self-fertilisation, however, as the species appears highly self-incompatible: although pollen grains will germinate on flowers of the self plant, they apparently fail to produce pollen tubes that penetrate the style. Even where cross-pollination does occur, fertilisation rate is fairly low. It is speculated that this is related to "a variety of chemical reactions at the pollen-stigma interface".

Cone production varies a great deal from year to year, but, as a result of its low flowering rate, is generally very low. However, there are typically a very high number of follicles per cone, leading to relatively high seed counts. There is some seed predation, primarily from the curculionid weevil

Weevils are beetles belonging to the Taxonomic rank, superfamily Curculionoidea, known for their elongated snouts. They are usually small, less than in length, and Herbivore, herbivorous. Approximately 97,000 species of weevils are known. They b ...

'' Cechides amoenus''.

Response to fire

Like many plants in

Like many plants in south-west Western Australia

Names such as the South West or South West corner, when used to refer to a specific area of Western Australia, denote a region that has been defined in several different ways.

Such names now usually refer to areas immediately south of the Pert ...

, ''B. prionotes'' is adapted to an environment in which bushfire events are relatively frequent. Most ''Banksia'' species can be placed in one of two broad groups according to their response to fire: ''reseeders'' are killed by fire, but fire also triggers the release of their canopy seed bank

A canopy seed bank or aerial seed bank is the aggregate of viable seed stored by a plant in its canopy. Canopy seed banks occur in plants that postpone seed release for some reason.

It is often associated with serotiny, the tendency of some plan ...

, thus promoting recruitment of the next generation; ''resprouter

Resprouters are plant species that are able to survive fire by the activation of dormant vegetative buds to produce regrowth.

Plants may resprout from a bud bank that can be located in different places, including in the trunk or major branches (e ...

s'' survive fire, resprouting from a lignotuber

A lignotuber is a woody swelling of the root crown possessed by some plants as a protection against destruction of the plant stem, such as by fire. Other woody plants may develop basal burls as a similar survival strategy, often as a response t ...

or, more rarely, epicormic buds

An epicormic shoot is a shoot growing from an epicormic bud, which lies underneath the bark of a trunk, stem, or branch of a plant.

Epicormic buds lie dormant beneath the bark, their growth suppressed by hormones from active shoots higher up ...

protected by thick bark. ''B. prionotes'' is unusual in that it does not fit neatly into either of these groups. It lacks a lignotuber or thick bark, and so cannot be considered a resprouter; yet it may survive or escape some fires because of its height, the sparseness of its foliage, and because it occurs in dune swales where fire are cooler and patchier. On the other hand, it is not a typical reseeder either, because of its relatively low fire mortality rates, and because it is only weakly serotinous

Serotiny in botany simply means 'following' or 'later'.

In the case of serotinous flowers, it means flowers which grow following the growth of leaves, or even more simply, flowering later in the season than is customary with allied species. Havi ...

: although fire promotes seed release, seed release still occurs in the absence of fire.

The actual degree of serotiny and fire mortality in ''B. prionotes'' varies with latitude, or, more likely, climate. Observations suggest that it is always killed by fire in the north of its range, which is relatively hot and dry, and where individual plants are usually smaller, but may survive fire in the cooler, moister, south. Moreover, it is essentially non-serotinous in the south, since all seed is released by the end of the second year, but seed retention increases steadily to the north, and at the northern end of its range, it typically takes around four years for a plant to release half of its seed in the absence of bushfire, with some seed retained for up to 12 years.

A number of other characteristics of ''B. prionotes'' can be understood as secondary responses to weak serotiny. For example, winter flowering ensures that seed is ripe by the beginning of the bushfire season; this is very important for weakly serotinous species, which rely heavily upon the current year's seed crop. Another example is the deciduous florets of ''B. prionotes''. In strongly serotinous species, the old florets are retained on the cones, where they function as fire fuel, helping to ensure that follicles reach temperatures sufficient to trigger seed release. In ''B. prionotes'', however, seed release is triggered at relatively low temperatures: in one study, 50% of follicles opened at , and 90% opened at ; in contrast, the closely related but strongly serotinous ''B. hookeriana'' required respectively. Floret retention would therefore be to no advantage, and might even prevent seed from escaping spontaneously opened follicles.

Seed release in ''B. prionotes'' is promoted by repeated wetting of the cones. The seed separator

A seed separator is a structure found in the follicles of some Proteaceae. These follicles typically contain two seeds, with a seed separator between them. The seed separator is nothing but a little chip of wood, but in some cases it serves an i ...

that holds the seeds in place is hygroscopic

Hygroscopy is the phenomenon of attracting and holding water molecules via either absorption or adsorption from the surrounding environment, which is usually at normal or room temperature. If water molecules become suspended among the substance ...

; its two wings pull together then wet, then spread and curl inwards as it dries out again. In doing so, it functions as a lever, gradually prying seeds out of a follicle over the course of a wet-dry cycle. This adaptation ensures that seed release following fire is delayed until the onset of rain, when germination and seedling survival rates are higher.

Because of its higher susceptibility and lower reliance on fire for reproduction, the optimal fire interval for ''B. prionotes'' is higher than for other ''Banksia'' species with which it occurs. One simulation suggested an interval of 18 years was optimal for ''B. prionotes'', compared to 15 years for ''B. hookeriana'' and 11 years for ''B. attenuata''. The same model suggested that ''B. prionotes'' is quite susceptible to reductions in fire intervals. On the other hand, it shows little susceptibility to increases in fire interval: although senescence and death are often observed in plants older than about 30 years, healthy stands have been observed that have escaped fire for 50 years. These stands have a multi-aged structure, demonstrating the occurrence of successful inter-fire recruitment.

Fire response may also furnish an explanation for the evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

of this species. The differences in fire regime between dune crests and swales would have created different evolutionary pressures, with plants on crests adapting to frequent hot fires by becoming strongly serotinous, and plants in swales adapting to patchier, cooler fires with weaker serotiny. Speciation would be made possible by the much reduced genetic exchange between crest plants and swale plants, although evidence suggests that there was some introgression

Introgression, also known as introgressive hybridization, in genetics is the transfer of genetic material from one species into the gene pool of another by the repeated backcrossing of an interspecific hybrid with one of its parent species. Intr ...

at first. Eventually, however, the need for weakly serotinous plants to produce ripe seed by the bushfire season would have brought forward its flowering season until the flowering seasons no longer overlapped; thus a phenological

Phenology is the study of periodic events in biological life cycles and how these are influenced by seasonal and interannual variations in climate, as well as habitat factors (such as elevation).

Examples include the date of emergence of leaves ...

barrier to exchange was erected, allowing the two populations to drift

Drift or Drifts may refer to:

Geography

* Drift or ford (crossing) of a river

* Drift, Kentucky, unincorporated community in the United States

* In Cornwall, England:

** Drift, Cornwall, village

** Drift Reservoir, associated with the village

...

independently of each other.

Conservation

''Banksia prionotes'' issusceptible

Susceptibility may refer to:

Physics and engineering

In physics the susceptibility is a quantification for the change of an extensive property under variation of an intensive property. The word may refer to:

* In physics, the susceptibility of a ...

to a number of threatening processes. It is highly susceptible to ''Phytophthora cinnamomi

''Phytophthora cinnamomi'' is a soil-borne water mould that produces an infection which causes a condition in plants variously called "root rot", "dieback", or (in certain '' Castanea'' species), "ink disease". The plant pathogen is one of the wo ...

'' dieback; wild populations are harvested commercially by the cut flower industry

Cut flowers are flowers or flower buds (often with some stem and leaf) that have been cut from the plant bearing it. It is usually removed from the plant for decorative use. Typical uses are in vase displays, wreaths and garlands. Many gardener ...

; and some of its range is subject to land clearing for urban or agricultural purposes. An assessment of the potential impact of climate change on this species found that severe change is likely to lead to a reduction in its range of around 50% by 2080; and even mild change is projected to cause a reduction of 30%; but under mid-severity scenarios the distribution may actually grow, depending on how effectively it can migrate into newly habitable areas. However, this study does not address the potential of climate change to alter fire regime

A fire regime is the pattern, frequency, and intensity of the bushfires and wildfires that prevail in an area over long periods of time. It is an integral part of fire ecology, and renewal for certain types of ecosystems. A fire regime describes th ...

s; these have already been impacted by the arrival of humans, and this change is thought to have led to a decline in the abundance and range of ''B. prionotes''.

The species as a whole is not considered particularly vulnerable to these factors, however, as it is so widely distributed and common. Western Australia's Department of Environment and Conservation does not consider it to be rare, and has not included it on their Declared Rare and Priority Flora List

The Declared Rare and Priority Flora List is the system by which Western Australia's conservation flora are given a priority. Developed by the Government of Western Australia's Department of Environment and Conservation, it was used extensively wi ...

. It nonetheless has high conservation importance in at least one context: it is a keystone mutualist in the Avon Wheatbelt

The Avon Wheatbelt is a bioregion in Western Australia. It has an area of . It is considered part of the larger Southwest Australia savanna ecoregion.

Geography

The Avon Wheatbelt bioregion is mostly a gently undulating landscape with low reli ...

, where it is the only source of nectar during a critical period of the year when no other nectar-producing plant is in flower. The loss of ''B. prionotes'' from the region would therefore mean the loss of all the honeyeaters as well, and this would affect the many other species of plants that rely on honeyeaters for pollination. The primary vegetation community in which ''Banksia prionotes'' occurs in the Avon Wheatbelt is considered a priority ecological community, and is proposed for formal gazetting as a threatened ecological community under the name "''Banksia prionotes'' and ''Xylomelum angustifolium

''Xylomelum angustifolium'', the sandplain woody pear, is a tree species in the family Proteaceae, endemic to Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the la ...

'' low woodlands on transported yellow sand". Although currently in near-pristine and static condition, it is considered at risk due to a large number of threatening processes, including land clearing, landscape fragmentation, rising soil salinity

Soil salinity is the salt content in the soil; the process of increasing the salt content is known as salinization. Salts occur naturally within soils and water. Salination can be caused by natural processes such as mineral weathering or by the ...

, grazing pressure

Grazing pressure is defined as the number of grazing animals of a specified class (age, species, physiological status like pregnant) per unit weight of herbage (herbage biomass). It is well established in general usage.

Definition

Grazing pre ...

, competition with weeds, changes to the fire regime, rubbish dumping, and ''P. cinnamomi'' dieback.

Cultivation

Described as "an outstanding ornamental species" by

Described as "an outstanding ornamental species" by ASGAP

The Australian Native Plants Society (Australia) (ANPSA) is a federation of seven state-based member organisations for people interested in Australia's native flora, both in aspects of conservation and in cultivation.

A national conference is h ...

, its brightly coloured, conspicuous flower spikes make ''B. prionotes'' a popular garden plant. It is good for attracting honeyeaters to the garden, and sometimes flowers twice a year. A low growing dwarf form which reaches high is available in Western Australia, sold as "Little Kalbarri Candles".

It is fairly easy to grow in areas with a Mediterranean climate

A Mediterranean climate (also called a dry summer temperate climate ''Cs'') is a temperate climate sub-type, generally characterized by warm, dry summers and mild, fairly wet winters; these weather conditions are typically experienced in the ...

, but does not do well in areas with high summer humidity. It requires a sunny position in well-drained soil, and tolerates at least moderate frost. It should be pruned lightly, not below the green foliage, as it tends to become straggly with age otherwise. Seeds do not require any treatment prior to sowing

Sowing is the process of planting seeds. An area or object that has had seeds planted in it will be described as a sowed or sown area.

Plants which are usually sown

Among the major field crops, oats, wheat, and rye are sown, grasses and leg ...

, and take 21 to 35 days to germinate